Today’s talent deficiency is tomorrow’s imperative.

Susan W. Christensen is a managing director in the talent and organization practice at Accenture’s North America Resources operating group. Sandra L. Jones is managing director in Accenture’s Utilities industry group. Brian Payne is a managing director within Accenture’s Utilities talent and organization practice. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Karen Brennan-Holton, Scott Cisel and William Ernzen.

Utilities face immediate and unprecedented operational challenges – from asset failures to regulatory pressures – and they’re all exacerbated by a growing dearth of critical skills needed to effectively run today’s andtomorrow’s utility. Utility companies typically have been more reactive than proactive in the area of talent development and retention, and the result is an effect on their bottom line as well as their ability to meet operational, safety, and customer expectations.

At one U.S. utility, last-minute sourcing of capital construction work led to a 25 percent spending increase on a precious budget of only a couple of hundred million dollars. Failure to plan and secure resources associated with known asset investments proved to be a costly error for this utility. But even where cost pressures are manageable, other risk factors can be onerous. At another company, the markout-and-locate function was handled externally by providers who lacked the adequate internal skills to oversee and ensure the work would be performed correctly. In situations like these, the utility compact’s mandate for safety calls management to take action.

As Accenture authors Kelly Gallant, Timothy Porter, and Jack Azagury pointed out in these pages earlier this year,1 the future is shifting. The utility’s role and its growth potential are becoming less clear. This demanding landscape is requiring companies to identify and find new resource types, and develop new relationships in order to obtain the critical skill sets necessary to meet the shifting environment.

For example, in a recent conversation, an executive at a large U.S. utility said he found “daunting” the challenge of finding individuals who possess the analytical capabilities required to leverage the vast amounts of data from the utility’s smart metering implementation. As a result, the utility expects this gap to reduce the effectiveness of leveraging data as planned.

This evolving environment and need for talent also presents newly coined roles, such as the “data scientist.” Such changing needs for talent happen at a pace much quicker than universities’ ability to adapt, nurture, and produce qualified graduates.

According to a 2013 Conference Board CEO Challenge survey, human capital was cited as the No. 1 most critical challenge by executives in Europe and Asia – but not so by North American respondents.2 For North American utilities, this lack of prioritization and responsiveness around workforce strategies bring consequences, namely increased costs, increased risk, and decreased customer satisfaction. What’s viewed as a deficiency today will become an imperative tomorrow.

Companies with this foresight are acting now. Utilities that want to remain or become more successful must prepare and execute accordingly. The plan for talent acquisition, internal skills development, and supplemental support from external entities needs to be carefully architected within a cost-balanced framework and a keen eye for business in the future. Those that prepare well and effectively execute the plan stand to improve effectiveness and efficiency, reduce costs, and mitigate their operational risks.

Prioritizing Talent

Many issues and challenges within and outside the industry already are affecting utilities and their workforces, or they will in the next three to five years. This situation underscores the need to move the focus on talent higher on the priority list, especially so for skilled craft talent. Natural disasters such as Superstorm Sandy have many utilities intensifying their focus on evaluating electric infrastructure reliability and the associated cross-company operating model to manage through these types of outages. Many companies now are relying on contractors as partners to assist them in restoration efforts due to internal shortage of manpower. The San Bruno explosion, as well as other incidents, has given rise to significant pressure on the gas side of the industry from the U.S. Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), and general public opinion. Shifting customer expectations are driving utilities to take on new multichannel approaches to communicating with their customers, such as adding the use of Twitter, Facebook, text messaging, and chat to their call center capabilities.

Every one of these challenges brings with it an associated workforce effect. In many cases, the results have been costly, and in some instances, have affected share prices and service to consumers. The aftermath of Superstorm Sandy is a prime example. In the days, weeks, and months following the event, some utilities struggled with how to get labor across company boundaries, and create and execute the mutual assistance process. (See “Manpower Strategy for Mutual Aid.”)

In other cases, the challenge is potentially an opportunity. New technologies available today enable companies to look at different ways to execute work. For example, Procter & Gamble is leveraging technology and crowdsourcing3 models to innovate. These capabilities have enabled the company to solve R&D problems through partner organizations, individual contributors outside the organization, and employees. Additionally, new technologies such as Elance, oDesk, and TopCoder have created vast pools of independent, just-in-time, virtual workers with top skills and knowledge. While other industries are taking advantage of these ideas, many utilities have yet to fully embrace them.

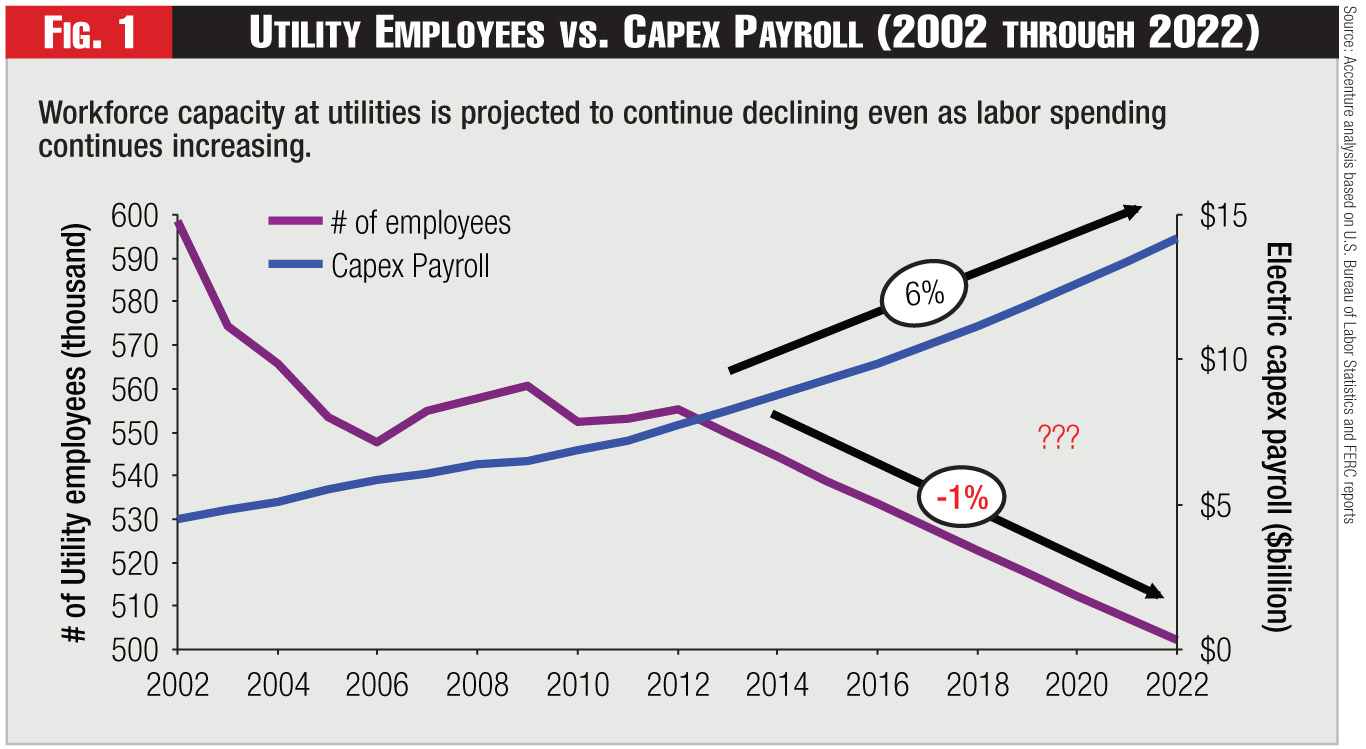

Utilities must also look to the needs of the future in a changing and uncertain industry environment. For example, capital spend is projected to increase as infrastructures across North America age and new build continues. Investments in energy-related capital projects forecasted by the International Energy Agency are to be $16.9 trillion globally by 2035.4 Translating this to talent, the gap is widening in North America over time, as the demand curve increases and the supply curve decreases, leaving utilities and similar industries with a shrinking skilled labor pool to draw from (see Figure 1). The question is, how will utilities stack up in this intense draw against other capital-intensive industries?

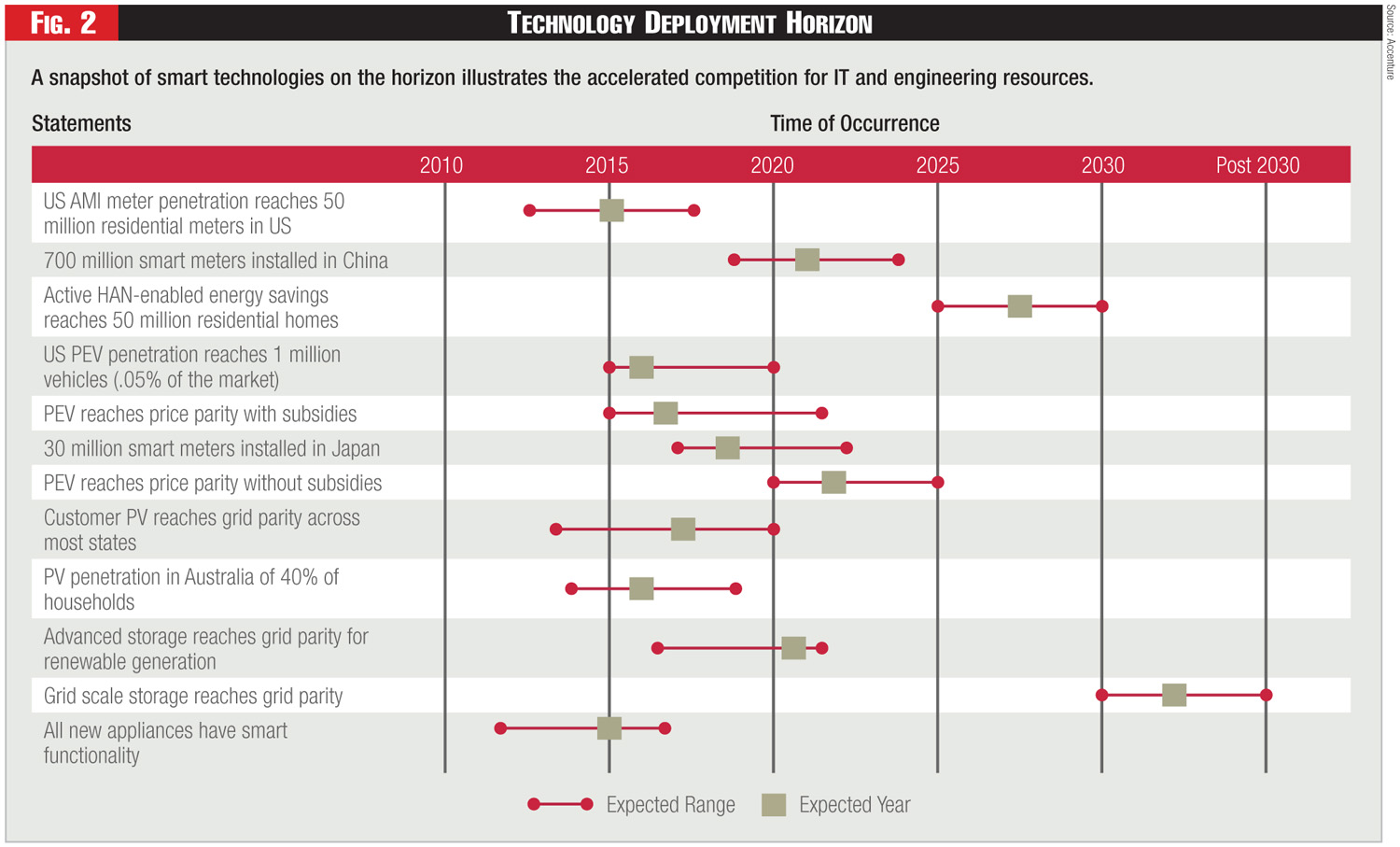

The talent gap also is accelerating within areas such as information technology (IT) and engineering, given the advancement of emerging technologies such as plug-in electric vehicles (PEV), compressed natural gas (CNG) vehicles, fuel cells, microturbines, smart grid, and photovoltaics (PV). (See Figure 2.)

In some cases the capabilities in demand are relatively new. For example, on the customer side, many utilities are evaluating how to change and shore up skills in areas such as marketing, social media, and analytics to address rapidly shifting customer demands. As these functions gain significance, it raises the question of how to build skills at the appropriate pace.

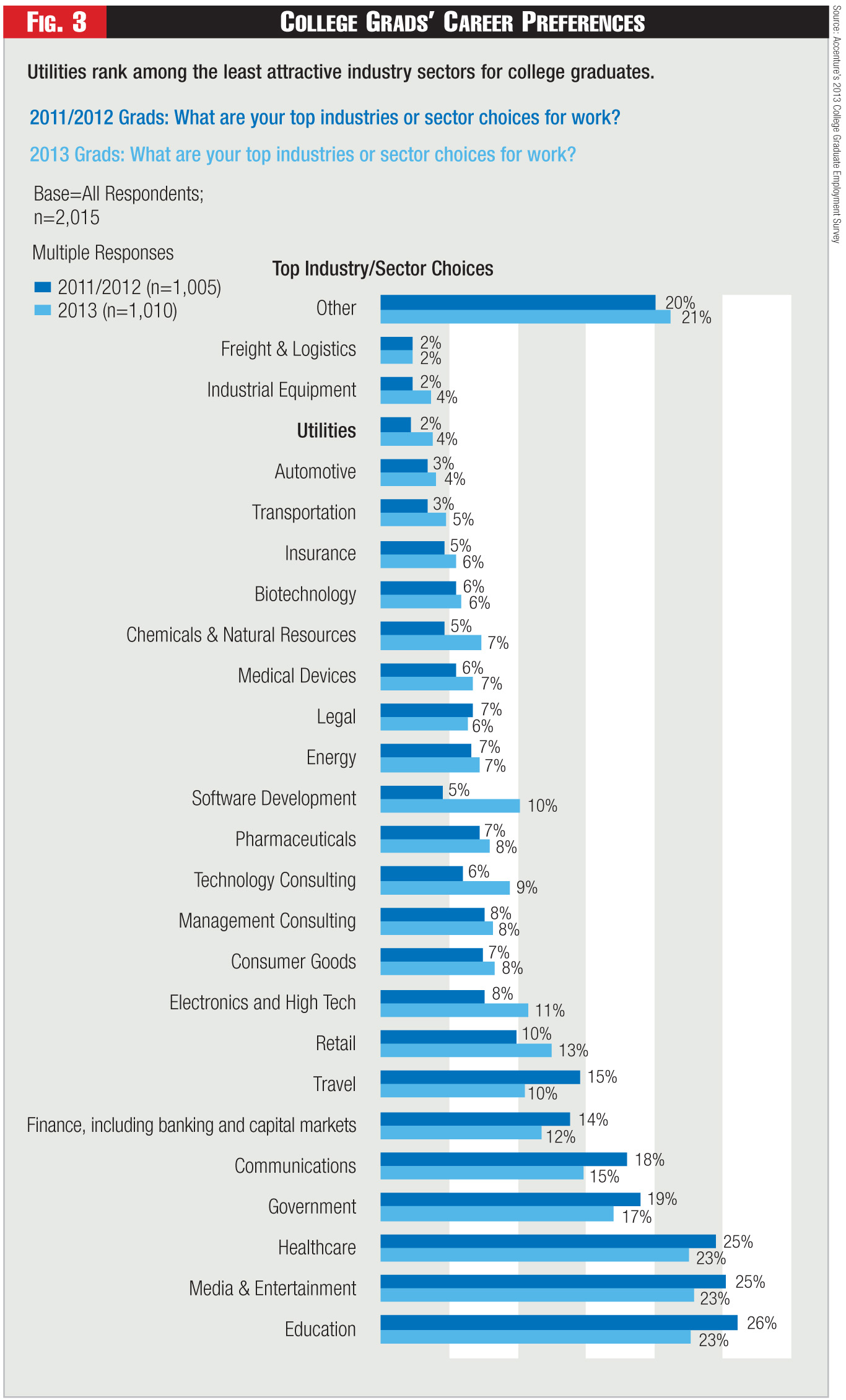

The same pool of talent that utilities must exploit to address their immediate and emerging challenges is also being targeted by organizations in industries that are perceived as more attractive. How do utilities get the right slice of talent when everyone wants to work at the Zappos, Googles, and Apples of the world? Even some oil and gas companies are creating a more attractive work and lifestyle environment that catches the attention of new graduates and young talent. The same can’t be said for most utility companies. The overall trend is reinforced in the findings of Accenture’s 2013 College Graduate Employment Survey,5 where utilities wasn’t only ranked close to last among interesting industries to work in, but has fallen in ranking from the 2011 and 2012 results (see Figure 3).

While companies in competing industries have already begun to see the value of developing long-term resource plans, many utilities continue to struggle to get theirs off the ground. For example, not one of the organizations ranked in the “Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work”6 in 2013 and 2012 was a utility – although several came from neighboring industries such as energy and natural resources. This lack of a plan drives many utilities to spend more on contractors, as a percentage, and causes a talent imbalance that’s hard to correct. Many have outsourced work to such an extent that they essentially are moving competencies and skills out of their business, and once lost, gaining them back will become extremely costly – if a utility can reacquire them at all.

Utilities should reflect on the competencies required to effectively run their businesses and assess the strategic importance of each. They should then identify which ones they are good at executing. Finally, they should determine the capabilities andcapacity of their current resources as well as how their talent pool is changing or needs to change.

In short, understanding the capability of a utility’s workforce and how to raise it to meet current and future needs is now, more than ever, a CEO-level concern. Utilities must become good at planning for and managing talent, inside and out, at an unprecedented pace. How does an organization become that good at something that fast?

Paradigm Transition

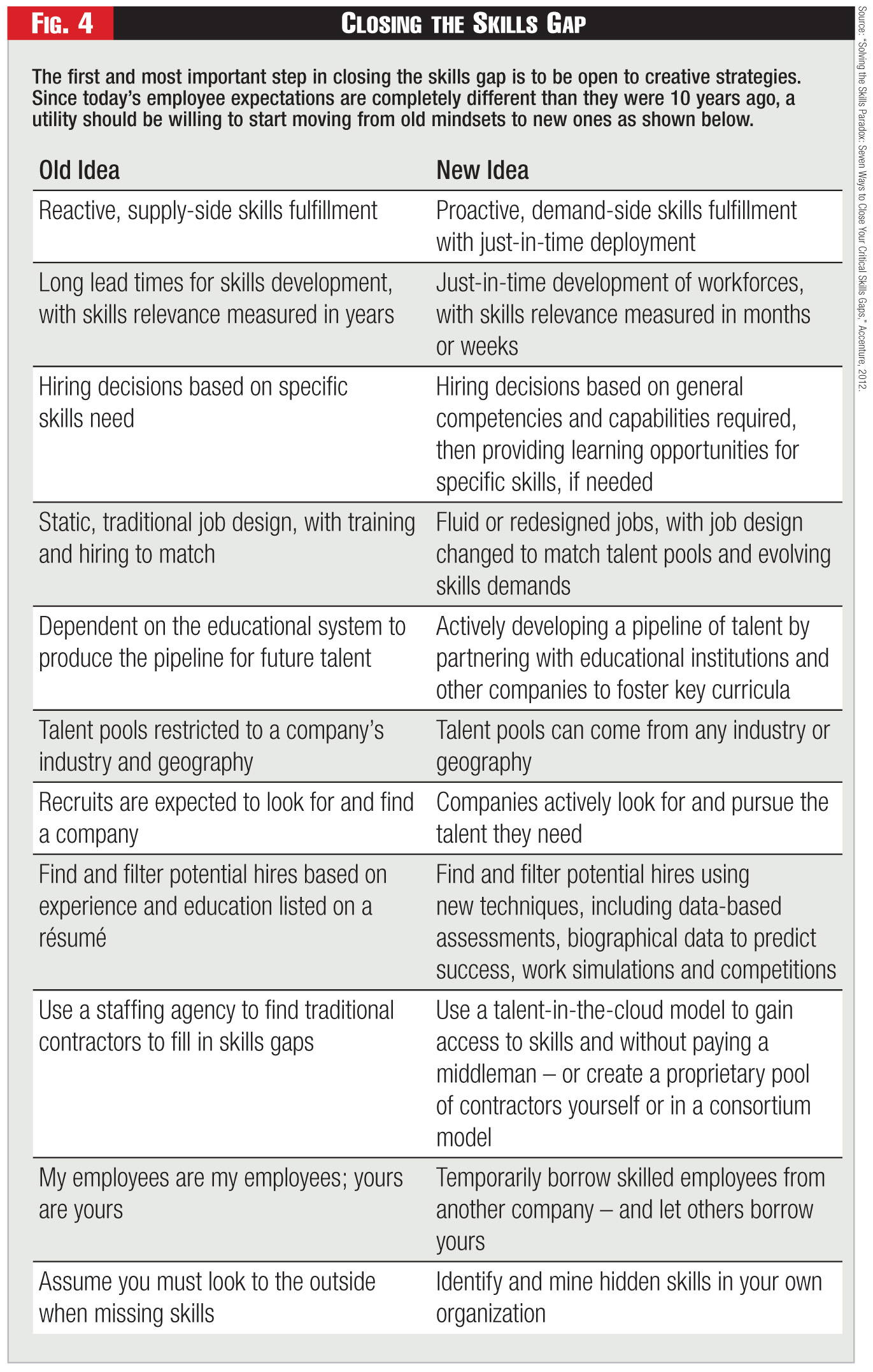

The solution is a robust workforce plan that strategically addresses the old paradigms and shifts an organization to the new way of thinking about human resources as a critical capability. This thinking includes a very prescriptive view of the extended workforce – the global network of outside contractors, outsourcing partners, vendors, strategic partners, customers, and other nontraditional workers at an organization’s disposal. By maximizing the potential of both an extended workforce and permanent employees, companies would gain critical advantages and minimize the risk of inability to serve.

It’s clear utilities will need to create new strategies that reflect new realities and create a new employee value proposition in order to attract, retain, and optimize their workforce. In addition to the paradigms needing to change, companies also need to examine their operating models for efficiency related to talent management. In many cases, fundamental issues about human resources and sourcing need to be addressed and resolved first. Two major issues in many organizations are that the people making the decisions across the company are poorly connected to the people in human resources, and few, if any, are focused on the future recruiting needs and workforce competition one year out, three years out, and 10 years out. As one utility executive stated, “The spray-and-pray approach to hiring will not work in the future.”

To define a workforce strategy for today as well as tomorrow, utilities need to recognize the link between the direction of their business strategy and their true workforce capability. If there’s no major strategy change planned, then are there projects of greater magnitude or variety that require special skills? And are those skills need for two years, five years, or indefinitely?

Answering this question and others drives a corresponding workforce plan with lead times and costs that might not be currently or adequately accounted for. As part of this process, a utility needs to put in checkpoints to enable the organization to shift as the market shifts. To support its workforce plan or strategy, a utility will need to set up planning processes, decision-making capabilities, an operating model, and a governance model to flex when needed and make appropriate decisions at the right points in time.

These requirements suggest taking four key actions.

First, evaluate your talent and workforce strategy in alignment with your current and emerging business strategy. Create a linkage between your business direction, asset strategy, and your workforce plan. You wouldn’t acquire a company without evaluating the financials first, so how can you take on a new business function or project without a clearly defined path for meeting the resource requirements? As part of this activity, map the resource requirements by volume, skill set, regional availability, cost to acquire, and other data points to the actual projects and business endeavors with as much precision as you would identify the price per share of an acquisition target. And then identify the scenarios that will force shifts as the future unfolds.

Second, decide what capabilities should remain in-house and what capabilities can be sourced externally. Recognize that the picture you forecast likely will look very different from what you have today. If it looks the same, you probably haven’t challenged your organization to be realistic. Utilities need to strategically determine where to maintain complete in-house talent and where to include the new extended workforce: a network of outside contractors, outsourcing partners, vendors, strategic partners, customers, regulators, and other nontraditional contributors to fulfill demand.

Next, evaluate the operating model and governance to position a tighter coalition between core operations, IT, procurement, and human resources on forecasting, sourcing, and deployment and development of both internal and external talent. This evaluation then needs to go a step further and consider defining how talent needs will be determined; how talent will be sourced, developed, and deployed; and at what pace and flex. Everyone has a role to play. The responsibilities can be aligned in different ways, but all of the responsibilities must be understood and owned by some part of the organization so that accountability can be assigned accordingly.

Finally, prepare leaders and hold them accountable to understand and lead these shifting dynamics. Assess and develop the appropriate leadership principles for your business direction to be successful. Just as with the ranks of the workforce, define a leadership strategy for developing, recruiting, and retaining the leadership talent that mirrors your company’s ambitions or critical imperatives. Once it’s clearly defined, drive it out in every communication and performance management opportunity available to build the culture your company wishes to possess. The success of the workforce overall is in the strength and consistency of the leadership team’s guidance. For example, if retention of engineers is a persistent issue, tie accountability for resolution to the vice president and director levels.

Delivering on Expectations

The stakes are rising. Utilities must decisively take steps today with insight and focus on the future of the corporate vision. Ultimately, defining a workforce strategy and plan is more than about improving; it could become the defining element that differentiates those who survive. By being proactive in workforce strategy, a utility can optimize its labor spend today (sourcing spend, talent acquisition costs, development costs, and the like) and be in a better position to deliver on the expectations of tomorrow.

Endnotes:

1. “Profit and the New Normal: Delivering value in a zero-growth market,” Public Utilities Fortnightly, June 2013.

2. The Conference Board CEO Challenge 2013.

3. Merriam-Webster defines “crowdsourcing” as the practice of obtaining needed services, ideas, or content by soliciting contributions from a large group of people, and especially from the online community, rather than from traditional employees or suppliers.

4. World Energy Outlook 2011 OECD/International Energy Agency 2011.

5. Accenture 2013 College Graduate Employment Survey.

6. Fortune “100 Best Companies to Work For,” 2013.

Category (Actual):

Department: