How to make sustainable performance improvements at any utility.

Cheryl Hyman until recently was vice president of operational strategy and business intelligence at Commonwealth Edison in Chicago. She’s now chancellor of the City Colleges of Chicago. Alan Feibelman is a partner in the energy practice at management consulting firm Oliver Wyman. Email him at Alan.Feibelman@oliverwyman.com. David Neville recently was a senior associate in the energy practice at Oliver Wyman.

Sustained performance improvement is often a difficult objective to achieve in a large company. Many such attempts involve various cross-functional initiatives that leave companies with unfinished projects, lower morale and disappointing results. Commonwealth Edison (ComEd) has found that the key to sustained performance improvement is the establishment of a cadre of high-potential managers to address company-wide initiatives full-time. Providing such a team with ample training, visibility and support from senior management can lead to long-term financial, operational, and strategic benefits, while simultaneously developing the next generation of leaders for the company.

ComEd Looks in the Mirror

In October 2008, ComEd Chairman and CEO Frank M. Clark initiated a strategy to improve financial and operational performance as well as customer service. The company already had a number of initiatives under way, but the concern was that some of the cross-functional initiatives lacked the dedicated resources and analytical rigor needed to make real changes. For example, major projects, including efforts to “fix the work management process” and “improve new business,” had been assigned to executives without dedicating significant staff resources and time to address the issues.

Another challenge was initiative overload. Every department had its own set of projects that lacked a cross-functional view. These projects often had competing priorities and even if implemented well, the projects could pull the company in different directions. Those initiatives that did impact multiple business units within ComEd lacked the high-level priority status needed for proper execution.

Clark and the executive team wanted to address the issue from a fresh perspective without becoming dependent on consultants. The result was the formation of ComEd Sustainable Solutions (CSS). The company selected eight high-potential managers with diverse skill sets who would identify, prioritize, analyze and address critical company issues. The team included managers with MBAs, engineers and members with expertise in regulatory and legislative affairs. Part of the plan was to assemble the team quickly to analyze ComEd’s most pressing strategic and operational issues.

To ensure team members brought a fresh perspective to the process, CSS members from ComEd’s transmission and distribution and operations groups were assigned to analyze customer operations, while managers from customer operations concentrated on T&D and operations issues. This approach also created an opportunity for CSS members to broaden their skill sets and knowledge.

The team’s initial efforts included interviews of 200 line managers and executives, which resulted in opportunities to refine the priorities of various initiatives already under way. CSS members also identified new areas to investigate and highlighted more than 16 new performance improvement opportunities.

Originally envisioned as a six-month initiative, the CSS team became the foundation for a transformation of ComEd business practices companywide.

‘Consultant-Lite’ Approach

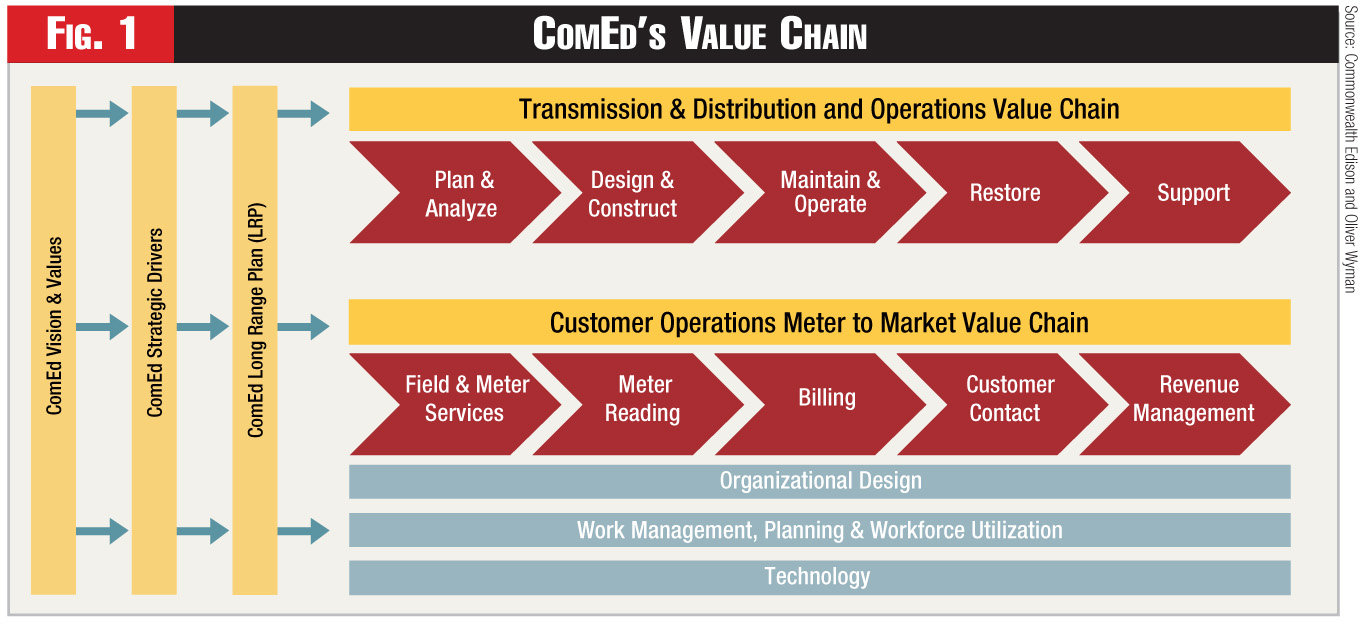

After more than 200 interviews, outside benchmarking and a site visit completed, the CSS team needed a structure to organize and prioritize its performance improvement ideas. The team created value chains for customer operations and transmission and distribution (T&D) to provide a common way of looking at these functions. For example, the primary links in the T&D value chain included: plan and analyze; design and construct; maintain and operate; restore; and support (see Figure 1). Critical issues and improvement opportunities were organized along the steps in the value chain and several initiatives were chosen for in-depth analysis and evaluation.

In Phase I of the project, the team analyzed long-standing, challenging cross-functional issues, such as revenue protection, storm response, work and contractor management and the budget process. Each initiative cut across multiple parts of the value chain and affected several groups within the company, while offering improvements in operations, finance and customer satisfaction. For example, the CSS team’s analysis of the company’s revenue protection efforts led to new ways to tackle the problems of energy theft, defective meters and consumption on inactive accounts. The results included new process designs, a new organizational unit and a significant financial benefit for the company.

Senior management also charged the CSS team with the task of creating a more analytical approach to improving the business while strengthening ComEd’s pool of analytical talent among its managers. ComEd partnered with Oliver Wyman, a strategy consulting firm, to institutionalize a structured approach to solving the complex, cross-functional issues that CSS was tackling. Oliver Wyman created a toolkit that included training modules on consulting best practices, such as problem structuring, presentation skills, project management and advanced training for Excel and PowerPoint software programs. The training facilitated ComEd’s goal of making CSS sustainable by reducing the need for additional consultant support.

The so-called “consultant-lite” approach proved successful for ComEd, because it provided the dual benefit of lowering consulting expenditures while creating internal consultants in the form of CSS team members. Furthermore, the success from Phase I of the project showed that this type of structure could offer long-term value if made permanent. After significant internal discussions as well as outside benchmarking, ComEd formed a new organizational unit, called operational strategy and business intelligence (OSBI). This group has a broader mandate than the original strategic initiatives team did. Modeled after successful strategy groups at eBay, Starbucks, and Fidelity Investments, the OSBI group consists of three teams: 1) strategic initiatives, responsible for cross-functional process improvement; 2) business intelligence, responsible for benchmarking, analysis and operational assessments; and 3) operational analysis and strategy, responsible for strategic planning, risk management and initiative monitoring and feedback.

This new group also consolidated key activities within ComEd, eliminating redundancies across several benchmarking groups, while also reducing the initiative overload issue. More important, the group has prioritized and scored initiatives from a variety of sources, linking these initiatives back to ComEd’s strategic drivers.

Playbook for Sustainable Improvement

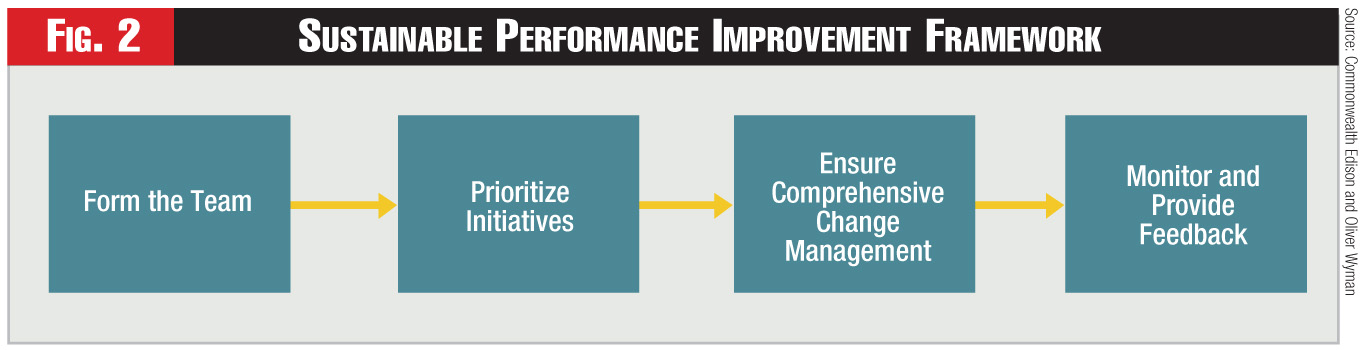

The work done at ComEd can be structured into a playbook, which is being explored elsewhere within Exelon and can be used at other utilities. Although some of ComEd’s circumstances were unique, other utilities also could adopt the company’s performance improvement framework to drive lasting, positive change in their organization. The suggested plan consists of a structured, four-step approach (see Figure 2).

The first step in the process involves creating a small team of six to eight high-potential managers to dedicate to the strategy and process improvement projects. This assignment is designed as a six- to nine-month developmental role. At the end of each project, new team members are rotated in. To encourage a fresh perspective and also to develop leaders’ management skills, managers are assigned to initiatives outside of their normal functional areas.

It’s also important to develop a pool of high-powered analysts for the company. Project leaders should hand-pick a few high-potential analysts, who are smart, energetic and data-oriented, to support the team. If such skills already exist in the utility, the team will be off to a solid head start. If not, newer analysts could be mentored by outside consultants to develop a solid foundation for supporting the strategic initiatives. The analyst role also should rotate, albeit with a slightly longer term than the manager rotation, perhaps one to two years.

A strong team, composed of both managers and analysts, is fundamental in the effort to make substantial performance improvements.

After forming a team, it’s critical to prioritize the initiatives to tackle in the first phase of the project. To provide sufficient focus and resources, the company will limit the number of high-level, strategic initiatives to six to eight per year. At any given time, half of the projects should be in analysis phase and half of the projects should be in execution or implementation phase. This doesn’t imply that these projects would be the only ones happening at the company. Tactical improvement projects could take place within individual departments. However, larger, cross-functional projects need dedicated teams and management focus.

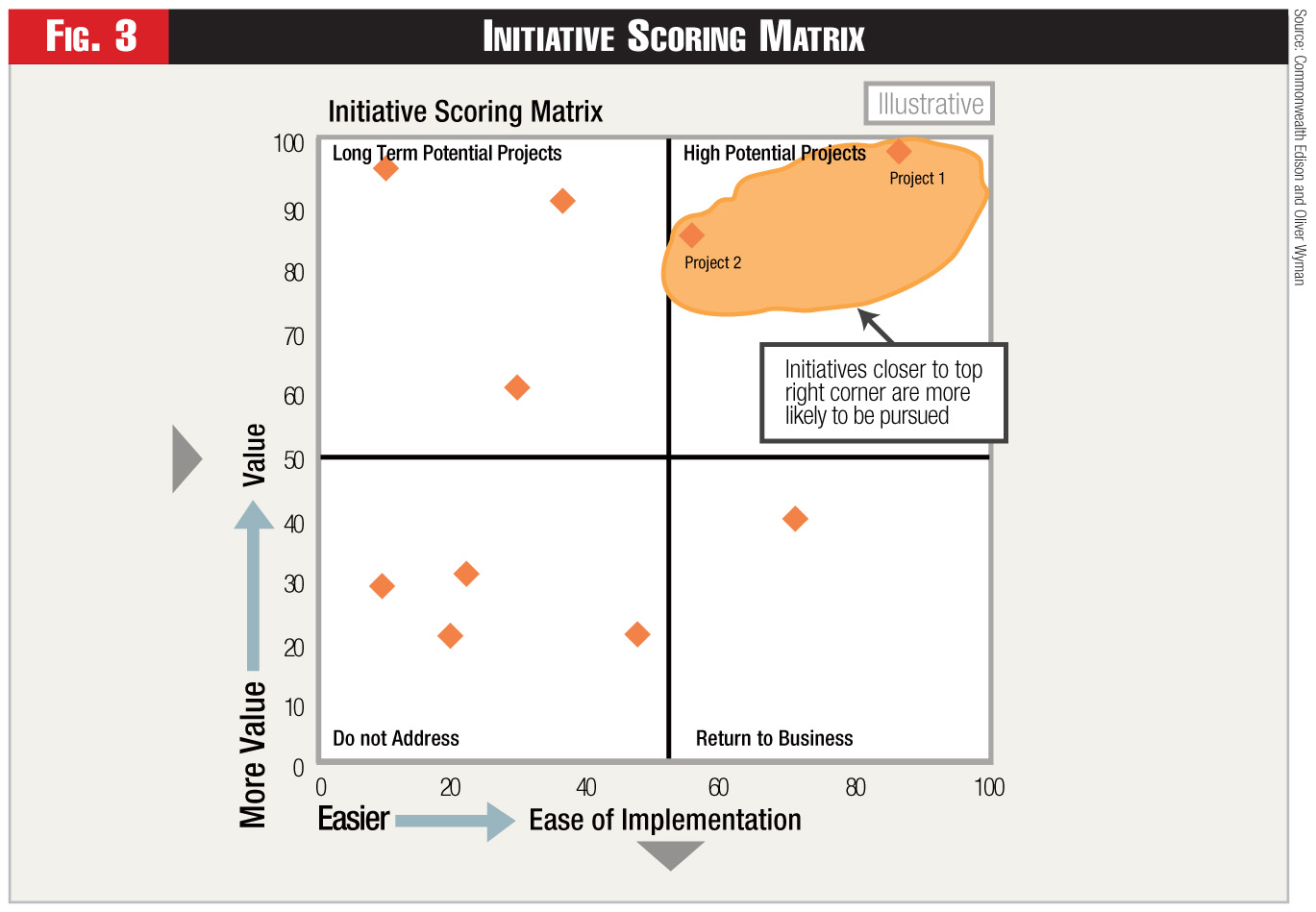

To prioritize initiatives, the team develops a robust scoring model linked to the strategic drivers of the company. For example, projects could be scored on their ability to enhance shareholder value, improve the customer experience, or improve operational efficiency. At ComEd, a 2 x 2 matrix of value versus ease of implementation was used, to summarize the priorities, with sub-components reflecting the strategic drivers of the company (see Figure 3).

A key to a successful internal improvement group is a partnership and close working relationship with business units (BU). BU leaders and line management need a voice and an ownership stake in the process. At ComEd, BU leaders meet regularly with the group and managers can propose initiatives online through an internal Web site. To score potential improvement initiatives, subject matter experts (SMEs) are employed from BUs to facilitate the decision-making process. Once a proposed initiative has been selected, these SMEs are involved in implementation of the project, providing credibility for the improvement team.

Along with strong BU working relationships, the team needs senior management visibility. This can be created through updates and presentations at senior leadership meetings. Strategic initiatives with the potential to deliver significant operational value are reviewed regularly by the senior executive team. At these meetings, the team is sponsored by a member of the senior executive team who can ensure that the team is empowered to deliver candid feedback while maintaining the ability to drive its change management initiatives forward.

A third key to success for an improvement group is an internal communications strategy focused on maintaining the linkage to the front line. For example, the ComEd OSBI team regularly communicated to first line managers and front line employees through monthly articles in the company newsletter. Each article highlighted a key initiative. OSBI also conducted briefings for the company’s key managers that focused on the link between ComEd’s vision and OSBI-led initiatives.

By gaining BU trust, seeking executive sponsorship and stressing internal communications, the improvement team has a much better chance of building buy-in and seeing its initiatives implemented. But once initiatives are implemented, how does the team ensure that changes will stick? Sustainable change needs a comprehensive feedback mechanism.

The feedback and monitoring process is often the most overlooked part of a performance improvement program. From the project team, there often is an over-the-wall mentality after hand-offs are made. From a management standpoint, it’s easy to claim victory and just move on. To ensure accountability, the improvement team should implement a strong feedback and monitoring mechanism. A new initiative should be returned to a BU only after a process is established to monitor the progress and evaluate appropriate metrics. At ComEd, each initiative returned to the business has a BU owner as well as an OSBI team contact. Senior management regularly reviews initiatives that have been returned to the business to ensure the functional management team is sustaining the changes made.

Talent, Trust and Morale

Implementing a sustainable performance team is not without challenges. The three main challenges involve accountability, morale, and talent.

In the initial phases of the project, BU managers often can be reluctant to trust the team with complex, cross-functional projects. The BU leader is accountable for the results of his or her division and bringing in outside challengers is difficult. Interestingly, this situation often reverses itself in later phases of the project. Once business managers begin to trust the improvement team, they often want to assign many of their improvement projects to the team. This can present a resource issue for the improvement team, but is a welcome challenge to address. The team can mitigate this risk through upfront and frequent communication and clear rules of engagement.

Morale also might suffer with the implementation of this type of cross-company initiative. Managers on the team could be seen as special, and with their careers on the fast track. This can lead to jealousy and even outside managers trying to undermine the team. Executive leadership can address this challenge by rotating members of the team and communicating the team’s mission to the entire organization. The performance team should not become a clandestine audit team. If the team’s mission is clearly communicated to the broader organization and the team has visibility to employees at all levels of the organization, these misconceptions can be prevented.

A third challenge to implementing this type of structure is talent. With the wrong type of analysts and managers on the team, the team could struggle to make real changes. Senior management should be extremely selective in staffing the team, focusing on managers with strong analytical, problem solving, and communications skills. Furthermore, senior management shouldn’t be afraid to change team members if one person isn’t pulling his or her weight. However, this should be done on a non-retribution basis. If an employee is selected for the team, that person shouldn’t be punished if they don’t succeed in this developmental role.

Despite the challenges, ComEd’s OSBI team has contributed to performance improvements in a variety of areas including strategic, operational, financial, and environmental. From a strategic standpoint, the OSBI team facilitated the development of the company’s strategic drivers. Through focused communications, employees are beginning to understand the link between the strategic drivers of the company and their day-to-day work. Operationally and financially, ComEd has reduced leakage and losses by redesigning metering processes, and has rationalized overtime and pre-staffing for storms without impacting CAIDI (customer outage duration). The OSBI project even provided environmental benefits for the company, through the development of a comprehensive transformer recovery program.

Beyond the strategic and operational benefits, the ComEd OSBI team has developed and enhanced the analytical toolkit of more than 30 ComEd managers. Some OSBI managers have rotated out of the department and are now managing projects in new line departments—many in a different area from their previous position—and are utilizing their improved analytical skills. Former OSBI managers also are expected to conduct training sessions with their new colleagues to pass on to the organization the skills they’ve learned.

It isn’t easy to make real, sustainable change happen at a large utility. The daily needs of the business, competing priorities and at times inertia, all could become obstacles. By creating a sustainable performance team, utilities can overcome these obstacles. The process doesn’t cost a lot of money, but requires an investment in dedicated resources, executive support and talented, analytically-oriented employees. The results are worth it and can put a charge in any utility’s performance.

Category (Actual):

Department: