Strategic transformation demandsmore than score-keeping skills.

Jim O’Connor is a principal with Archstone Consulting and is located in Chicago. Email him at joconnor@archstoneconsulting.com.

Financing the energy enterprise is a complex undertaking. Recent events suggest companies are looking to multi-talented CFOs—whether they have utility industry experience or not—to deliver more guidance to business operations. Several of the industry’s top-performing companies—for example, Energy Future Holdings (the former TXU), Exelon, and Sempra Energy—have been guided by CFOs with an expansive sense of what the finance office should offer to the business.

Increasingly CFOs are developing the skills and capabilities to move beyond the traditional role of traffic cop to the more valued roles of business partner and enabler.

Improvement Mavens

Former Exelon CFO John Young recently became CEO of Energy Future Holdings. Young’s appointment marks the second time the big Texas utility has tapped an enterprising CFO for the CEO position. In early 2004, former Entergy CFO John Wilder was named CEO of TXU. Through outsourcing, asset sales and other restructuring efforts, Wilder strengthened the company’s balance sheet before last year’s dramatic takeover by KKR and Texas Pacific Group. Wilder was comfortable with these sorts of big, transformative initiatives because, while serving as the Entergy CFO, his team partnered with business leaders to meet the operational imperatives of cost effectiveness and improved risk management.1

What’s notable about Young is in his previous role as president of ExelonGeneration, he managed its nuclear,fossil and hydro operations and also had responsibilities for Exelon’s Power Team, overseeing power trading and marketing operations. Far from being limited to simple utility accounting skills, Young has deep experience with the revenue-generating parts of the energy business, which is invaluable knowledge for the debt-laden Energy Future Holdings.

That same dynamic is at work outside of Texas as other leading CFOs view themselves as improvement mavens.

SunEdison in September 2007 appointed utility industry outsider, Carlos Domenech, as CFO. While SunEdison is North America’s largest solar-energy services provider and isn’t a traditional utility, demand for its services within the sector is growing rapidly. Like Wilder before his appointment as CFO of Entergy, Domenech didn’t have energy industry experience. Instead, Domenech was CFO at Universal Pictures’ International Entertainment, where he led its integration with NBC and managed financial reporting across 25 countries. In praising Domenech’s experience, SunEdison’s CEO highlighted his “diverse industry experience with multi-national enterprises and expertise in supply chain.” Reading between the lines, the SunEdison CFO will play a part in strategic business improvement. Bean counters need not apply.

Finally, consider Sempra Energy’s Mark Snell, another CFO with extraordinary business improvement success.In a CFO Magazine article published in July 2007, Snell described how his charge—the Sempra trading, generation and commodities operations that grew fivefold in five years—accounts for more than 50 percent of Sempra’s income. The rest comes from the company’s SoCal Gas and San Diego Gas & Electric utility businesses. Again, a traditional CFO with a score-keeper mentality coming from a finance organization might not have seen and seized the opportunities.

CFOs After Enron

What makes these executives different is their willingness to offer strategic options and capabilities to their business brethren. In the world of diversified energy, CFOs need skills and experiences outside the traditional finance job descriptions of fiscal policemen, cost-center administrators and transaction processors.

So what has happened to change the CFO’s role and value proposition? Certainly external events like the Enron collapse, Sarbanes-Oxley legislation and the establishment of the Public Accounting Oversight Board have renewed finance’s resolve and focus on the basics—namely, getting the books right. But even while board members and business leaders are requiring CFOs to excel at those needs, they also want the CFO’s assistance with other business goals—data integrity and transparency, analytic capabilities, and project prioritization. Trends in the energy and utilities industry—the evolution of the services company, demand for transparency from regulators amidst ongoing regulation evolution, the need for multiple books (FERC, GAAP), and the driving need for more information by the business (e.g., insightful project and work management reporting)—further validate the need for improved CFO office capabilities that simply can’t be accomplished within the traditional scorekeeper attitude. The finance organization must nail the basics—controls and scorekeeping—yet provide energy companies the improved reporting and analysis capabilities to keep up with these other trends.

Today’s energy environment dictates that the finance office needs to drive significant improvements in corporate-wide efficiency and effectiveness, while simultaneously evolving to that revered and elusive role as a strategic partner to the operational business.

New Finance Toolbox

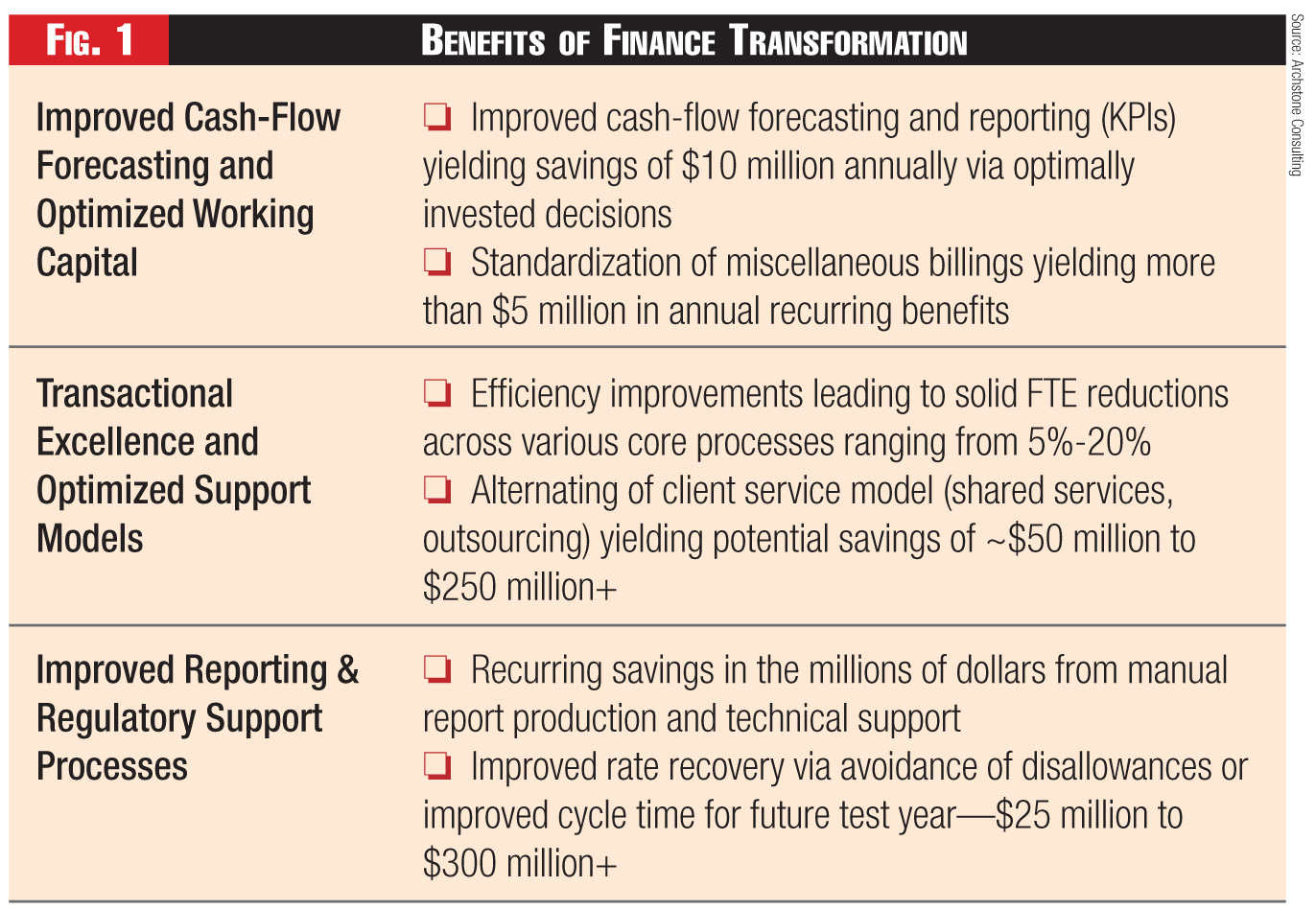

It’s nearly impossible to know exactly which financing and operational tools leading CFOs have used to earn their seat at the strategy table, but improved transactional excellence, cash-flow management and a reliance on enhanced reporting likely played crucial roles.

In the area of transaction excellence, the CFO office is leading efforts that reduce overall administrative cost structures through labor arbitrage and process improvements (outsourcing or shared services). Moves by TXU and others, for example, generated drastic work process and cost structure changes—saving about $150 million annually in the case of TXU — after Wilder became CEO. Improvements within most diversified utility business service units could realize double digit millions (or more) in annual savings, depending on their current state and how much changes.

Improving cash-flow forecasting and reporting can yield millions in project savings annually through optimized investing decisions. Other more traditional and tactical approaches that build on transactional excellence can improve cash flow from payables and retail billing operations. There often are opportunities to save millions within smaller, yet abundant miscellaneous billing efforts.

Finally, CFOs are automating their companies’ reporting capabilities to focus on transparency, ease of multiple views (such as GAAP, FERC and cash) to drastically improve rate-case preparation and reporting processes. That alone can save millions by improving the rate of recovery in regulatory hearings. Avoiding disallowances and speeding recovery through future rate-case filings may generate appreciable returns depending ona company’s situation. There are documented cases of project savingsin the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Roadmap

Knowing where a company wants to go is the first step in drawing a roadmap. Finding a driver—the CFO who isn’t afraid of bumps and potholes to be faced—is another.

Once the business case is made and points of arrival are clear, the CFO must engineer how the transformed finance function takes shape. The CFO must be dedicated to a lengthy transformation that occurs over time and in conceptual phases. Typically, the finance office is first viewed as a transactional scorekeeper. Once it demonstrates technical competency, it’s viewed as a guardian and commentator, particularly on facts of historic relevance to the organization. Only after evaluating facts through statistical and analytical tools and offering solutions is the finance function considered an advocate and partner to business units.

CFOs striving to evolve toward this more strategic role start by changing their skills and the skills of those around them. Once executive management decides to ask its finance department for strategic counsel, leaders in a good finance organization naturally will adapt to the new requirements and surround themselves with the right people for effecting needed changes (see sidebar “Recommended Reading”). But organic transformational change isn’t enough. Most leaders need the discipline provided by a structured program, so they often develop a competency model that matches their goals, industry issues and situation (see Figure 1). The competencies typically include technical, organizational and communication skills.

The second step toward transformation is an honest assessment of staff relative to the road map and future needsof the organization. As talent manager, the CFO creates development plansand subsequent training programs.

Finally, a structured development plan essentially provides a successionand advancement plan. The executive who has made it through the appropriate—and stridently detailed—steps in the development plan is usually the next person in line for advancement when opportunities arise. After Young wentto TXU, Exelon announced it wouldfill the CFO office with talent fromwithin, namely Ian McLean andMatt Hilzinger. Most likely they were being groomed for years before theirpromotions.

As the utility industry rises to meet 21st century challenges, so must the finance office. CFOs like Domenech, Snell, Wilder and Young provide role models for other CFOs. They succeeded in transforming their organizations to perform the role of strategic counselor for their companies by virtue of changing the way their offices functioned. Today’s energy challenges require this sort of transformation.

Endnote:

1. “Wilder, CEO of TXU, Relates Lessons Learned from Utility Deregulation,” Oct. 19, 2004, McCombs School of Business.

Category (Actual):

Department: