Increasing risks call for a new generation of leaders.

Jeff Hyler (jhyler@spencerstuart.com) is a member of executive search firm Spencer Stuart’s global energy practice in Chicago and specializes in the energy utility industry. Bob Shields (rshields@spencerstuart.com)also specializes in the energy utility sector and manages the Chicago office of Spencer Stuart.

Years ago, the electric utility industry was a much simpler place to do business. The typical utility delivered reliable electricity to a fixed geographic area at a regulated price. Operational, regulatory and financial risk topped the utility CEO’s agenda, and keeping regulators and shareholders happy—and the lights running—was a good blueprint for success.

The recent escalation of commodity price, environmental and political risks has changed everything. With energy needs rising, and no cohesive national policy to guide utilities in meeting the growing demand, utility CEOs face the unenviable task of strategizing for a market that will be shaped largely by the unpredictable future decisions of politicians.

Can new nuclear power plants get approved? Will wind generators get production tax credits? Will West Coast companies be allowed to re-permit their hydro plants? Will cap-and-trade legislation endanger the coal industry? And who will pay for the transmission of renewable energy? These critical questions still remain unanswered, but utility companies must forge a businessstrategy through the murk.

However, we do know a few things. Some form of climate change legislation is on the way. Commodity prices arelikely to continue to rise. The infrastructure is aging and new transmission and generation must be built to meet demand. Consumer electricity costs could, according to some estimates, double in the near future. And the capital markets are in distress.

As the industry’s senior leaders near retirement age, there’s an urgent need for a new generation of utility CEOs to step in and lead their companies through this increasingly complex and uncertain time. In a landscape where uncertainty is the only certainty, the CEO’s key role has been transformed into that of an enterprise risk manager. The role requires different skill sets than the ones that industry CEOs traditionally relied upon—but just how different will vary from company to company in response to specificcircumstances and challenges.

Strategic Alignment

Unlike in the past, there is no prototypical utility and, therefore, no prototypical CEO.

The “ideal” CEO for each company is one whose skill set matches the company’s current and long-term business strategy.

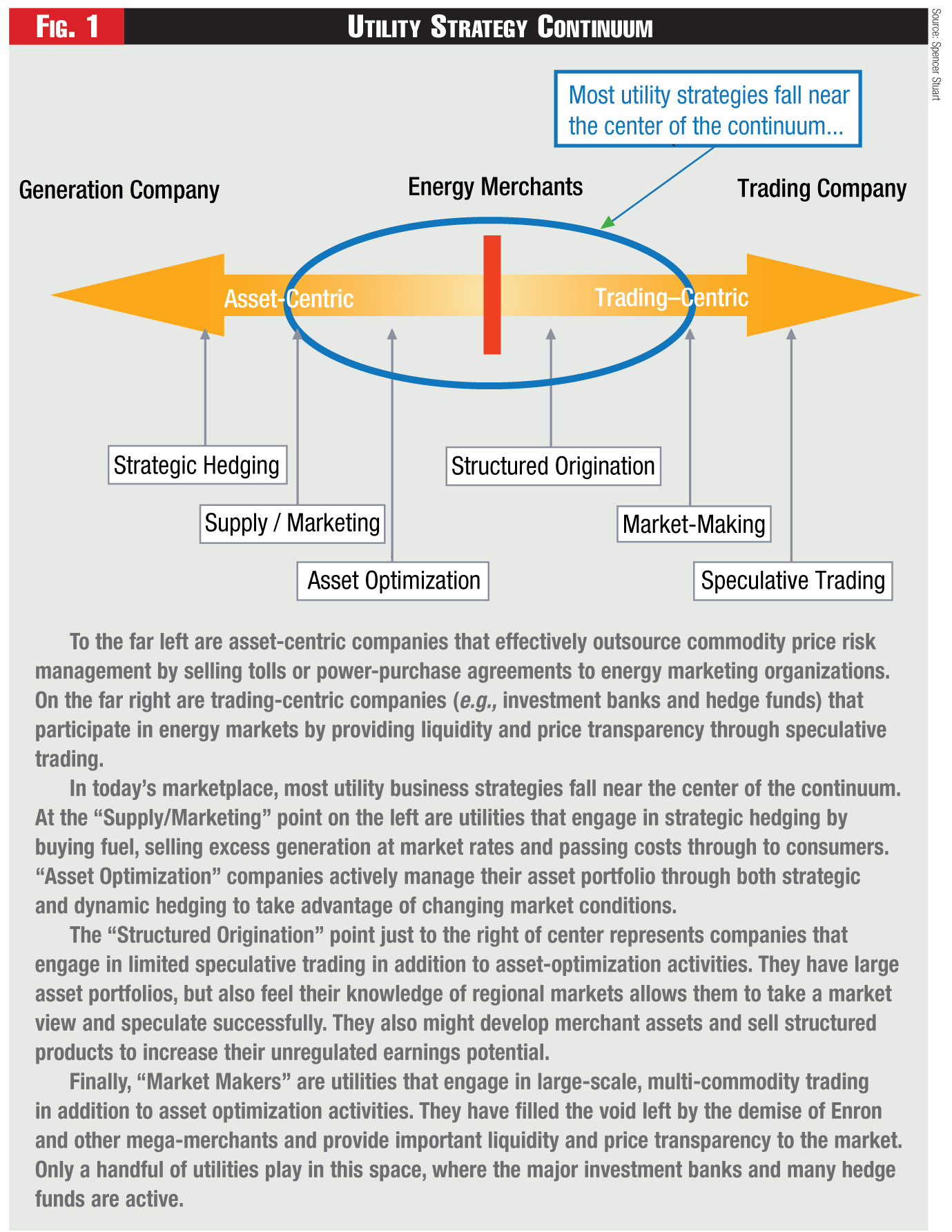

Companies can help to define their talent needs by looking at the utility marketplace as a continuum (see Figure 1) and identifying where their business strategy falls on the continuum.

Those companies that choose to operate on the left side of the continuum, where regulatory and operational risks are of most concern, can continue to recruit leaders who are particularly strong in regulatory affairs and utility operations. These companies may be content to stay in regulated markets because they’re in regions where ongoing population expansion will allow them to continue growing earnings and meeting shareholder expectations.

With fewer housing starts, many utilities are finding it difficult to meet growth expectations by relying solely on organic growth. Taking on more risk through unregulated ventures enables these companies to generate higher returns than they could if they were totally beholden to regulators. As a result, most utility companies today are positioned somewhere near the middle of the continuum. And for these companies, a broader CEO skill set is needed.

No longer is it enough for boards to choose CEOs who are masters at managing operational risk. Chief executives also must have the financial acumen to manage ongoing investor relations, deal with volatile commodity price risk, articulate a growth strategy that delivers enhanced shareholder value and be credible with Wall Street in articulating the value of the company’s unregulated activities.

Nowhere will financial acumen be needed more than in the financing and construction of new generation. This need will not only relate to financing issues—which will be significant—but also to sophisticated decision-making about fuel choice, risk management and hedging strategies.

In a future environment characterized both by increased M&A activity and by balkanized regulatory jurisdictions, the notion of regulatory complexity won’t soon go away, either. So it is also valuable for CEOs to have some legal experience, or at least understanding, to navigate this complexity.

A recent Spencer Stuart analysis of 25 of the nation’s largest utilities confirmed that organizations are favoring CEOs with legal and financial experience. Eighty percent of sitting CEOs have held a legal or finance role at some point in their career. Only 28 percent have held an engineering role, one of the traditional sources of senior leaders for the industry. This trend likely will continue into the future. The majority of talent for the center of the continuum won’t be bankers, and won’t come from traditional utility roles. Rather, talent will come from somewhere in between, most likely coupling operations experience with financial savvy that includes a deep understanding of market risk and portfolio theory.

For those companies that position themselves to the right on the continuum, the need for financial expertise is even greater. While these companies likely will still prefer candidates with utility industry experience, they’ll also need talent with the financial acumen to successfully articulate their strategy, value proposition and enterprise risk management program to key stakeholders such as investors, regulators and ratings agencies.

Developing Senior Leadership

Those companies to the left on the continuum are grooming senior talent much as they always have: by preparing high-potential executives with functional and operational roles of increasing responsibility. But the majority of utility companies at the center and to the right on the continuum are taking a different approach. Realizing the need for strong financial and legal understanding in the chief executive role, they’re moving executives such as the general counsel or CFO into an operations role (such as the COO or head of a business unit) before their elevation.

During the late 1990s, it seemed as though everyone viewed traditional utility experience as a liability. Following the collapse of Enron and the dramatic shift toward “back to basics” strategies, a large number of CEOs were promoted from within. Today, we’re still seeing a strong preference for internal candidates—and appropriately so—but more boards of directors are responding to shareholder pressure by conducting a more diligent CEO succession process. Many companies are benchmarking internal candidates for CEO succession against a well-qualified slate of external candidates. While many companies don’t intend to conduct an actual search,this CEO benchmarking process helps organizations to identify promising external talent and to pinpoint the strengths and weaknesses of their executive bench. This approach allows them to more strategically build the leadership team with an eye to the future.

While companies should expose their most talented senior executives toexperiences that will groom them for a future CEO role, there are limits to what most utilities can do. The industry’s workforce is aging and young talent isin high demand. These circumstances,combined with the ever-increasingcomplexity of the industry and the ever- broadening skill set it demands, virtually guarantee that utility companies will have difficulty finding a candidate who offers every desired competency.

As a result, boards must carefully consider not only CEO succession, but the strategic development of a senior leadership team. As companies look at the major areas of risk they must manage—from the traditional operational, regulatory and financial risks to the more recent commodity price, environmental and political risks—their senior ranks should contain leaders who, collectively, can cover all of these areas.

Part of the reason the industry has evolved to favor CEOs with legal and financial backgrounds is today’s complex regulatory, political and financial landscape. But another reason is that utility companies also traditionally have very strong operational executives upon whom these CEOs can rely.

After all, a CEO isn’t an individual with a checklist of skills. He or she is, first and foremost, a leader. While financial and regulatory understanding is important, executing the strategy requires the communication and leadership skills that are the hallmark of every successful CEO. It also requires the ability to attract, develop and retain a sophisticated senior team that can manage the full spectrum of increasingly complex risk.

A keen executive intelligence—the capacity to think clearly, analyze situations, and make the right decisions—isa critical trait for the CEO as well as for the members of the senior team he or she assembles. Given the business unit and jurisdictional complexity of thetypical utility, organizations need several executives who are ready to step up to the next level.

Hedging Talent

For companies that do it best, succession planning is a comprehensive approach to developing management talent throughout the organization. It is one of a handful of essential duties of the lead or nonexecutive director, but it is also a topic that should remain an ongoing priority for the board and appear regularly on its meeting agenda.

No one can predict which risks will have the biggest impact on future business operations. But constant executive assessment and development can position companies to have the talent in place to handle any scenario. In a world of constant and ever-multiplying risk, it’s the best way for utilities to hedge their bets.

Category (Actual):

Department: